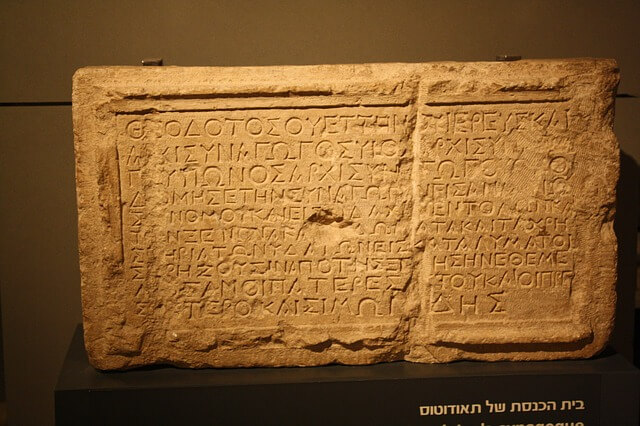

We’ve come across a number of ancient languages through the years that we haven’t been able to decipher. One of these examples date back to 1886 when British archaeologist Arthur Evans found a stone that held inscriptions in an unknown language. Now, the inscriptions were deciphered completely with the help of machine learning.

In time, Evans found similar inscriptions throughout Crete and dated them to be from around 1400 BCE.

That date means that those inscriptions were the earliest form of writing that was ever discovered. Evans, along with others, determined that the tablets they came across were written in different scripts – they called the oldest Linear A, which they dated to have been written between 1800 and 1400 BCE. The other one, Linear B, appeared sometime after 1400 BCE.

The architect and many others who followed him tried to decipher the language for years but it was only in 1953 that linguist Michael Ventris managed to crack the Linear B.

Ventris assumed that the writing was actually an early form of the Greek language and that the words that repeated themselves on the stone tablet were actually the names of various places on the island of Crete. All of his assumptions proved to be correct and allowed him to decipher the language.

However, Linear A still remained a mystery that baffled linguists up to this day.

Here is where Jiaming Luo and Regina Barzilay from MIT, alongside Yuan Cao from the Google AI Lab, come in. The team developed a machine learning system that can decipher long-lost languages.

The machine is fed with databases of text of a specific language and then searches through the text and identifies what words appear most often next another word. These paired up words make up meanings, such as king – man + woman = queen.

Luo and the team are looking into how language can change and evolve over time, how the related words still maintain the same order of characters and so forth. By keeping these rules in focus, the machine can decipher a language more easily, provided that it knows what the ancestral language is.

The researchers tested the machine on Linear B and Ugaritic, an early form of Hebrew that was discovered in 1929. The machine translated both of them accurately.

“We were able to correctly translate 67.3% of Linear B cognates into their Greek equivalents in the decipherment scenario,” the team said. “To the best of our knowledge, our experiment is the first attempt of deciphering Linear B automatically.”

All the attempts to decipher Linear A with ancient Greek as the progenitor language have failed so far, so the researchers might try to attempt to crack it by feeding it into every ancestral language the machine operates on.

If that will work, it remains to be seen but, if it does, it would be a huge, priceless achievement.

Follow TechTheLead on Google News to get the news first.