We’re thinking about re-usability more than ever before nowadays. One of the main problems with re-usable rockets, such as SpaceX’s Falcon 9 for example, is all the stress put on their legs when they land back down and that often causes damage. The solution to that problem could be… origami.

Re-thinking the way the rocket’s legs are built should make a difference and the researchers at the University of Washington turned to the old art of origami for answers and investigated how metamaterials could be structured in order to respond in different ways to impact forces.

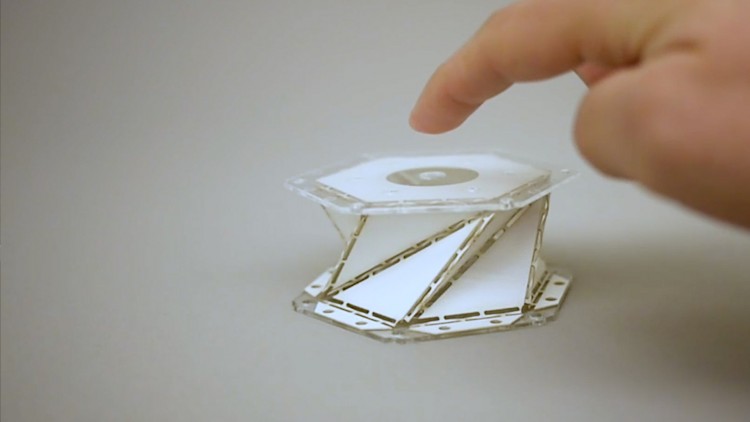

The team created a paper model of a metamaterial using folding creases that “promotes the forces that relax stresses in the chain.”

“If you were wearing a football helmet made of this material and something hit the helmet, you’d never feel that hit on your head. By the time the energy reaches you, it’s no longer pushing. It’s pulling,” Jinkyu Yang, a UW associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics, explained.

“Metamaterials are like Legos. You can make all types of structures by repeating a single type of building block, or unit cell as we call it,” Yang said. “Depending on how you design your unit cell, you can create a material with unique mechanical properties that are unprecedented in nature.”

So Yang and UW aeronautics and astronautics doctoral student Yasuhiro Miyazawa turned to origami in order to create their cell.

They used a laser cutter to cut across dotted lines into paper where it’s supposed to be folded, in the shape of a cylindrical structure. They glued acrylic caps on both ends and connected the cells into a chain.

They lined up 20 cells afterwards and connected one end to a device that applied pressure, capturing the reaction of the material via six GoPro cameras.

As expected, the origami cell chain performed very well: the force applied at one end never made it all the way up to the end of the chain. It was replaced instead by the tension force that started as the unit cells propagated faster down the chain.

The only time the unit cells at the end felt any of the tension was when it was pulling them back.

“Impact is a problem we encounter on a daily basis, and our system provides a completely new approach to reducing its effects. For example, we’d like to use it to help both people and cars fare better in car accidents,” Yang went on to say. “Right now it’s made out of paper, but we plan to make it out of a composite material. Ideally, we could optimize the material for each specific application.”

The team published their result in the Science Advances journal.

Follow TechTheLead on Google News to get the news first.