[adrotate group = “15”]

Before Metroid Dread, I had never played a game from the Metroid series, 2D or 3D. I had played metroidvania games – Hollow Knight and Ori, for example – and those have been some of my favorite gaming experiences in recent memory. With all the hype of Metroid’s return as well as my affinity for the metroidvania genre, I was excited to jump in.

Metroid Dread did not disappoint. In fact, it surpassed all my expectations.

Metroid Dread takes series protagonist Samus Aran to planet ZDR, where mysterious but powerful parasites X are allegedly found. In previous entries, Samus had destroyed all X lifeforms (or so they thought), as well as the Metroids, an equally dangerous parasite which was the natural predator to X. On ZDR, Samus quickly becomes overtaken by antagonist Raven Beak and has to find her way back to her ship. On her way to the surface, she has to avoid reprogrammed EMMI robots who, under Beak’s orders, are seeking to extract Samus’s Metroid DNA in order to regenerate the bioweapon.

The X parasites reappear, threatening the galaxy.

For the most part, Metroid Dread plays like a typical metroidvania. Start with an underpowered character, traverse a non-linear but connected world, gain new powers, and backtrack to find even more powers and paths.

While the game does not linger far from the formula the series helped create, that’s kind of a great thing. Metroid Dread has been incubating for 19 years at this point and the results really show. In many ways, Dread takes the metroidvania formula and polishes it to a level that has not been seen yet.

Take the world exploration. This element is a key component to metroidvanias as the world, not NPCs or story, guides the player to the next point, next powerup, and next pathway. The layout of planet ZDR does a great job of leading you to where you need to go next. The only paths forward are the ones you can reach with your current loadout. Upon gaining a new power, new paths open up, clearly labeled by either the color of your weapon or an icon. The game’s gates open and close throughout the story, naturally guiding the player to the right places at the right times.

Sometimes, the right pathway is hidden rather than blocked off. The Metroid series has a penchant for hidden blocks, and while not my favorite design element, they are overall well implemented throughout the game. Sometimes, the game naturally gets you curious about a one block gap between your path and one you can see. Other times, it strategically places enemies along the wall, asking you to shoot at them and reveal the hidden blocks behind. While excessively used throughout the game, I appreciate the intentional design choices which help players find the hidden blocks.

But these elements are to be expected – that’s kind of the point of metroidvanias. It’s the sequence breaks, getting items before their natural progression or going a way thought to be prohibitive, that makes metroidvanias so appealing. Without them, the game would only have one pathway forward, essentially turning the meandering experience of exploration into linear progression.

Timing a parry is so satisfying!

Metroid Dread is full on sequence breaks – many of which fans are currently finding – but one in particular stands out. If players are able to get the bomb before a certain boss fight, they can skip the second phase of the fight entirely. Not only that, but there is also a fully animated scene accompanying it. The fact that there is animation to the sequence break illustrates that the developers knew about the sequence break beforehand and kept it in.

Not only that, but they also intentionally designed the game for sequence breaks to be a part of the larger gameplay experience. It’s a little reward for players who walk off the beaten path. It’s the developers tacitly accepting the game’s audience, one who enjoys the exploration metroidvanias naturally create. Few metroidvania games acknowledge the player’s creativity in the same way.

Beyond elements of exploration, it’s clear the team put in effort to make every part of the game shine. The animation, in particular, needs to be noted. Samus moving around the world, jumping, hanging off ledges, shooting, dashing, etc. all feel so carefully crafted. Parrying is intensely satisfying as the camera suddenly zooms in, illustrating the impact of the well-timed parry and giving the player a chance to strike back. The attention to detail is tangible.

Animations are incredibly fluid with both fight and narrative sequences seamlessly transitioning from cutscene to gameplay. Some boss cutscenes even let you attack during them!

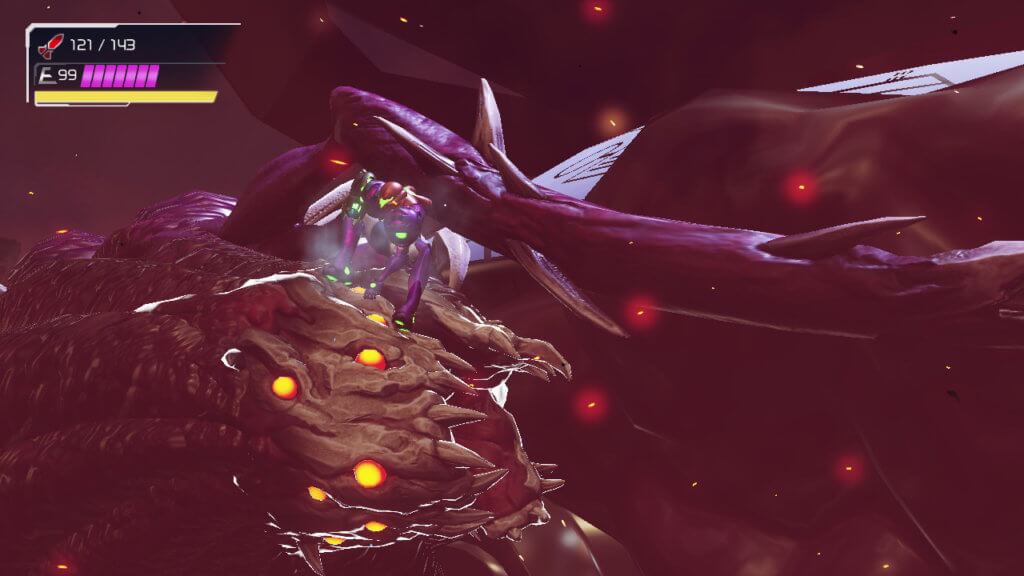

The narrative animations, too, help lend the game its shimmer. Sometimes, they occur naturally, moving from one location to another or running away from an EMMI. Parrying on certain or bosses can trigger an intense cutscene. Against one boss, Samus hands onto the head of the enemy, firing missiles all while the boss shakes its head vigorously to get Samus off. While limited, you still control able to shoot or parry during these cutscenes. Key to the experience is that they do not interrupt gameplay flow; they lead seamlessly in and out of exploration, or a battle, only heightening the immersion.

Speaking of immersion, the EMMI sections combined incredibly detailed sound and visual atmospheric elements to make a uniquely terrifying experience for a metroidvania games. In each world, the EMMI tracks Samus down in a restricted era. While you’re in there, the world gets gray, the sounds ominous, all while you are completely powerless against the EMMI chasing you.

It’s a stealth section in a game not traditionally known for stealth. But all elements – map layout, sound design, visual cues – play into the feeling of overwhelming dread.

The EMMI are terrifying and avoiding them adds a unique stealth mechanic to the series.

After finding all the powerups, barely escaping each EMMI, and making my way through the vast world, I had finally made it to the final boss. When the dust had all settled, I had won. Beaten the game. Satisfying as it all was, I wanted more.

In some cases, the sentiment of “wanting more” is to the game’s detriment. “Wanting more” can be a sign that the game is bare or incomplete, a not-so-uncommon experience in the current gaming landscape of half-baked game launches only completed post-launch through (often) paid DLC.

That wasn’t the case with Metroid Dread. I wanted more game because almost every aspect was so refined and polished. I wanted more because I wanted to continue exploring, traversing, and fighting. I wanted to experience more Metroid Dread. This was a sentiment of highest praise.

Since launch, reviewers, gamers, and the general online community have been heaping tons of praise onto Metroid Dread. Indeed, the torrent of high praise for a game in the Metroid series is unique in its sheer ubiquity.

But it’s not like this game gained this praise simply for being a legendary Nintendo franchise. While Metroid’s legacy has spawned an entire genre of gaming and remains one of Nintendo’s most important IPs, it often doesn’t get the love and attention it deserves. From both Nintendo and the general gaming community alike.

But Metroid Dread is different. Perhaps factors like the Switch’s overwhelming popularity comes into play. Maybe Nintendo’s aggressive marketing push finally broadened the interested audience for the game. Alternatively, it could have been the anticipation of a good game finally to come, with many recent games feeling half-baked or lackluster.

Instead, maybe it was some combination of factors which finally pushed Metroid from niche to mainstream.

Regardless of how or why Metroid Dread became a success, it is an unqualified success. It deserves the praise and attention its getting. For its overall game design, attention to detail in world building and animation, narrative arc, addicting gameplay loop, and more.

It may have taken 19 years but the queen of metroidvanias is back.

Follow TechTheLead on Google News to get the news first.